From the day we are born into this world, we’re told about what to do, what to wear, what to aspire to, what not to be. Your assigned gender at birth is filled with prerequisites and ideas of the colour of your clothes and how these utilities are constructed to fit your body are out of your control. There are conditions that are set out to as soon as you hit your first breath and gasp for air to fill your lungs; conditions of how you should look – but the ugly world that licks the soles of our feet pre-determine the beauty and bodily standards of what others might perceive you as.

How Africans view their bodies has totally changed since the time of colonisation. The attempt to dig through archives of art, oral stories and thrown away the history of how our ancestors looked, how they dressed, how they interacted with their sexuality before it was defined to them would take aeons to restore back into the norms of our social perceptions in this present moment. Queer bodies, before and now, are shaped and influenced by culture and context. Trans, gay, bisexual, pansexual, queer-identifying, non-binary, femme, fat, black/brown, disabled; all these bodies have been very vulnerable to the tides of social recognition and engaging with the ‘normality’ set by especially able-bodied cisgendered heterosexual people. I took the time to come to terms with how I identify at first, i.e., my body, and coming to terms with the bodies I’m sexually, emotionally, and spiritually attracted to, i.e., my sexual orientation.

With coming to terms with that, I pondered on the idea to document and archive the experiences of South African queer bodies from all backgrounds and looked at ways to see ourselves as heavenly, self-accepting and self-righteous – a middle-finger to dated ideologies and structures. We’re already being told who we cannot love, and how we shouldn’t love. Dismantling the ‘desired’ Instagram-esque body allows us to eliminate the toxicity and make way for us to celebrate our truest forms.

Queer Heavenly Bodies features 10 queer South Africans that are evolving with their bodies. They are learning, transitioning, becoming, being comfortable in the dissatisfaction of the cells that make up their matter. Curving the raptures attached to pronouns and labels of identification. I partnered up Maxime Michelet, a film photographer and activist from France who has descended into the uncared-for corners of Johannesburg to document African identities and landscapes and finding new stories to tell for the love of our concrete city.

We asked our 10 participants who carefully cover the spectrum questions about their names, how they identify, how they would describe the word ‘body’ in their own words, how they use their body to express their identity and how they navigate in society with these bodies...

Victor is a pansexual non-binary trans man. “Trans from female, not male”, says Victor. “For me, a body is a vessel. A political vessel. It allows me to be political about who I am.” In this meaning, we would describe a vessel to be a carrier. And for Victor, their expression helps them carry their identity. “My demeanour and the way I present help me insist on my identity. Because I was born in a different vessel, I am now being masculine in a female body. My identity as it is now is what makes me comfortable. This is why I don’t want to undertake gender reassignment surgery.”

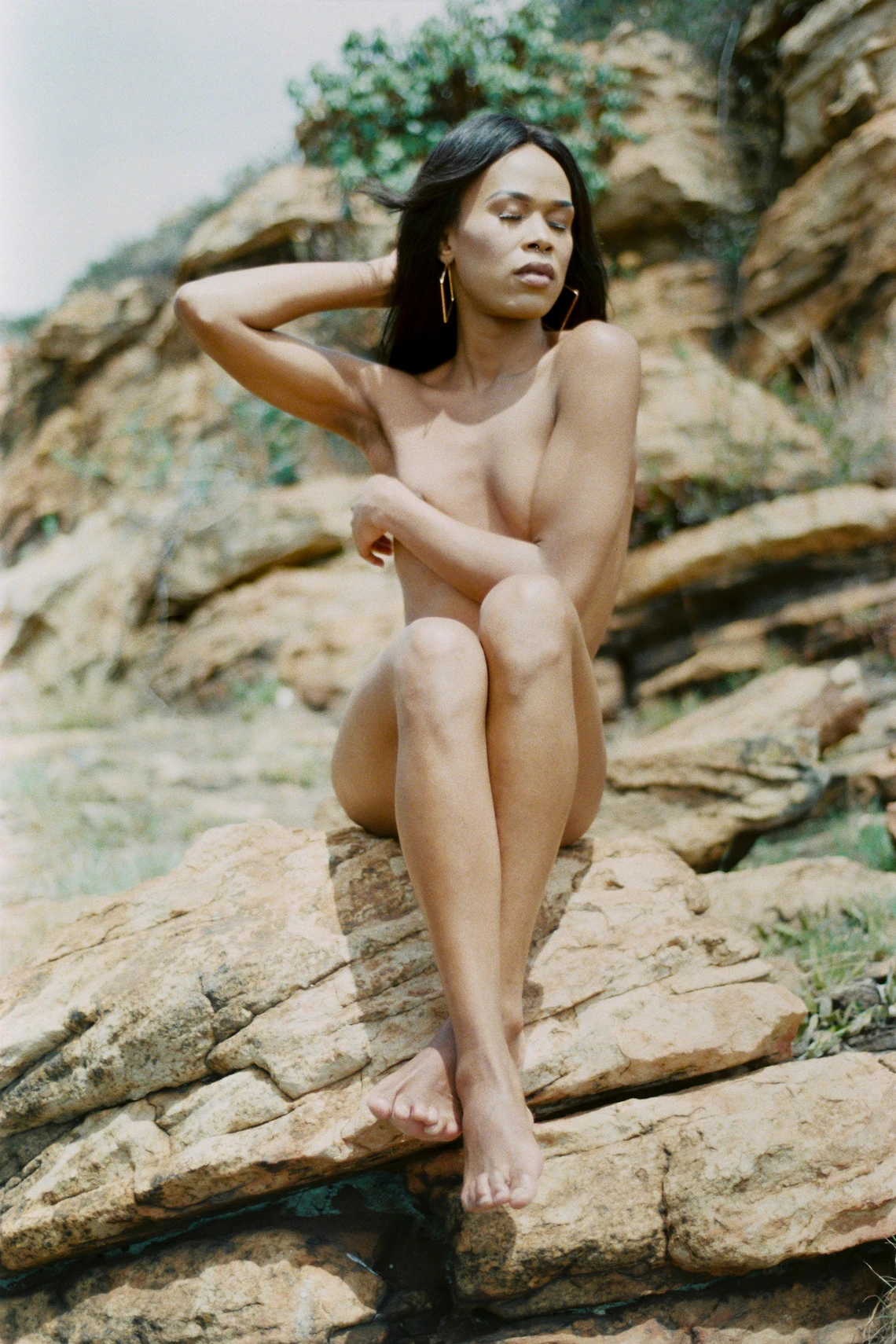

For Glow, she would describe herself as a T-Girl. “A body means being alive, being active. Being, simply being... I find that a lot of definitions of the body do not apply to me. My body is what I live in.”

The experiences of transgender women in our country mean having to constantly fight to exist. Trans bodies are living in a nocturnal half-dream, and fighting a revolution against societal norms of breaking stereotypes. “The difficulties queer bodies face are not the same for every type of queer. It is not a uniform experience. It is like there is a hierarchy in terms of lived experience. White gay men may face fewer difficulties than black queer women.” says Glow, profoundly. “As a trans person, I have the feeling that people sensationalise and make a big deal out of the word ‘trans’. I am trans because I went across the gender spectrum. But life, for every human being, is about being trans, about transitioning. When you get a tattoo, a piercing, or a new hair colour, you are trans, you are changing what you were before. Even when you get a car, you are not the same as you were before, you become trans to your old self.”

Kirsty identities as a Lesbian. “A body is the vessel of the soul. I don’t believe that when we die, we die. In my belief, you get put into another body if you haven’t completed what you were here for.” she speaks out.

“My body, with my tattoos and piercings is an artwork. I also try to be more muscular via exercising. I don’t want to look super feminine. When people look at me they think female, but not the average female, the girly girl. I rebel against the average female look.” Kirsty believes that being boxed and labelled should belong in the past. Much so like the following participant who stripped bare to showcase their body.

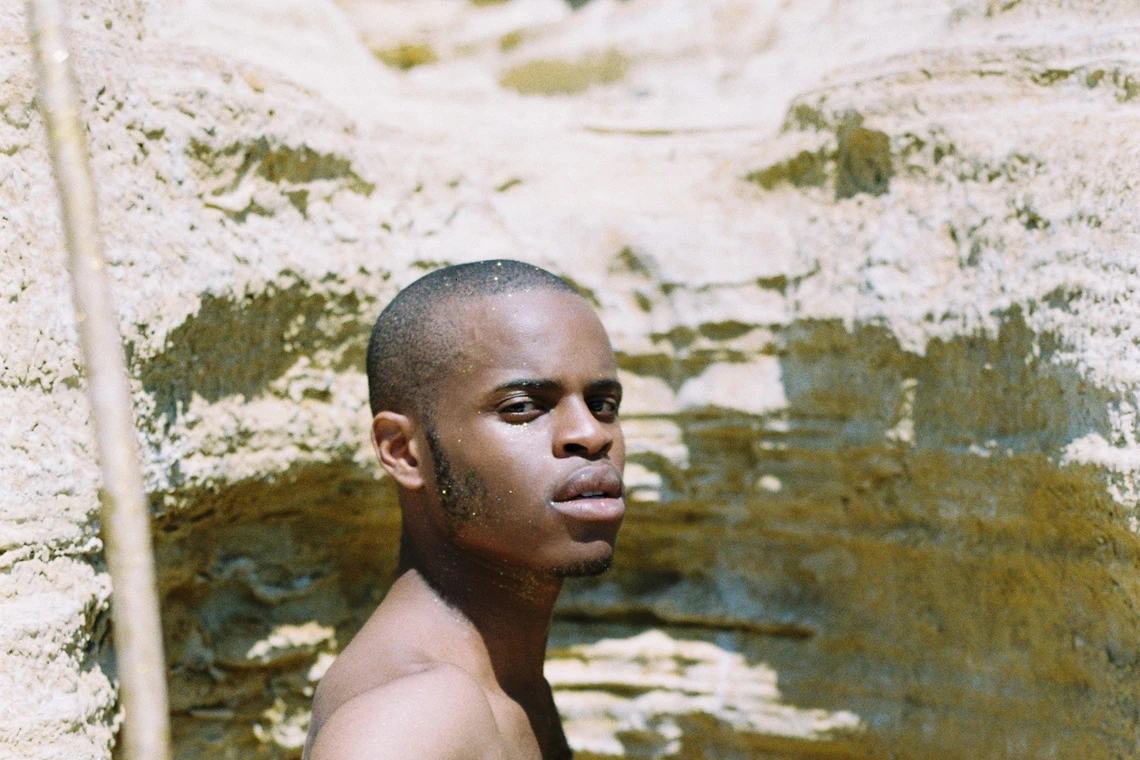

Kofi is a performance artist and identifies as Queer. He believes that his body is a concentration of energy. “With the art that I create, the way I dress, what I eat, how I keep in shape. Exercising especially allows me to have a flexible body, it maintains a proper energy flow, it allows the right interaction,” he says. The main challenges he faces in society right now is labelling – “ I also believe every human being born is queer, and we all eventually drift apart into labels. We are infinite beings.”

Embracing who we ought to be is a beautiful thing, and that’s why Izzy thinks that the way someone carries themselves or looks after themselves says a lot about who they are. Izzy identifies as a Queer Woman. “People always tell me I don’t look like I’m into women. What am I supposed to look like? I do use my body for attention; to attract compliments, especially my legs and my hair, but my personality too.”

“Christianity is a part of who I am so this ‘gay thing’ in my life has been complicated to deal with. I can live one way but my belief systems disagree with it.” The intersection crossroads of spirituality, religion and the institutions build around that is a thorn-barren path, especially when it comes to owning your truth and the way you experience your body as it grows. It’s no different for Hallie, who identifies themselves as female or femme.“ I am indifferent to other people’s gender. My body is my machine, my canvas. I use it to communicate my identity. I hope my identity goes beyond my gender. I also express my identity when I’m dancing”

When it comes to communicating about Queerness in the African sense, language becomes a barrier. Which is why we have to applaud the work that is being done by organisations such as Find New Words, a movement that’s taking South African languages and defining the LGBTQ+ terms. “The formula of communicating queerness is clumsy. If I don’t use the communally understood symbols of queerness, then my queerness is not comprehended. I can’t speak queerness in my own language.”

Much so, Bongani says that as someone who identifies as a gay man, “Fighting against how you’ll be perceived when you leave the door is a challenge. Wanting to be normal so people don’t notice you. Wanting to dim down what society wants to magnify…”

Gay men are often boxed into this one stream ideology of feminine and incapable of doing things that cisheterosexual men are. Gay men are often not that nice to each other, and that community along is divided with labels and stereotypes, with complex masculine fragility and shame. “The way I dress, the way I walk, the way I put myself together. I remember that in the past, I had a very feminine way of walking, and I used to try to walk more manly,” speaks Bongani.

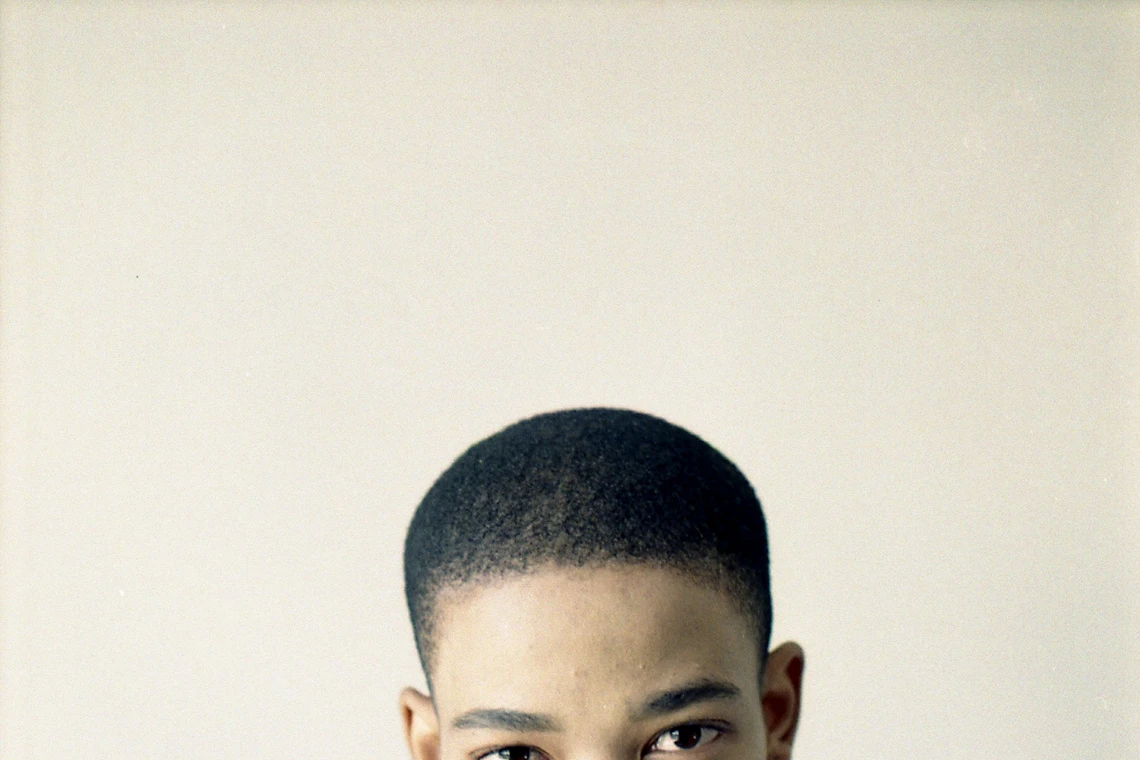

Lebo identifies as gay non-binary. “People have this mentality of how masculine and feminine things can be, but my mannerisms show who I am. I express myself the way I want to express myself,” He says. Lebo also expresses himself through the way he dresses, through style choices and being playful through that. “People have very lighted views on what is normal and what is not normal. Being queer means being unique. So show how flamboyant you are.”

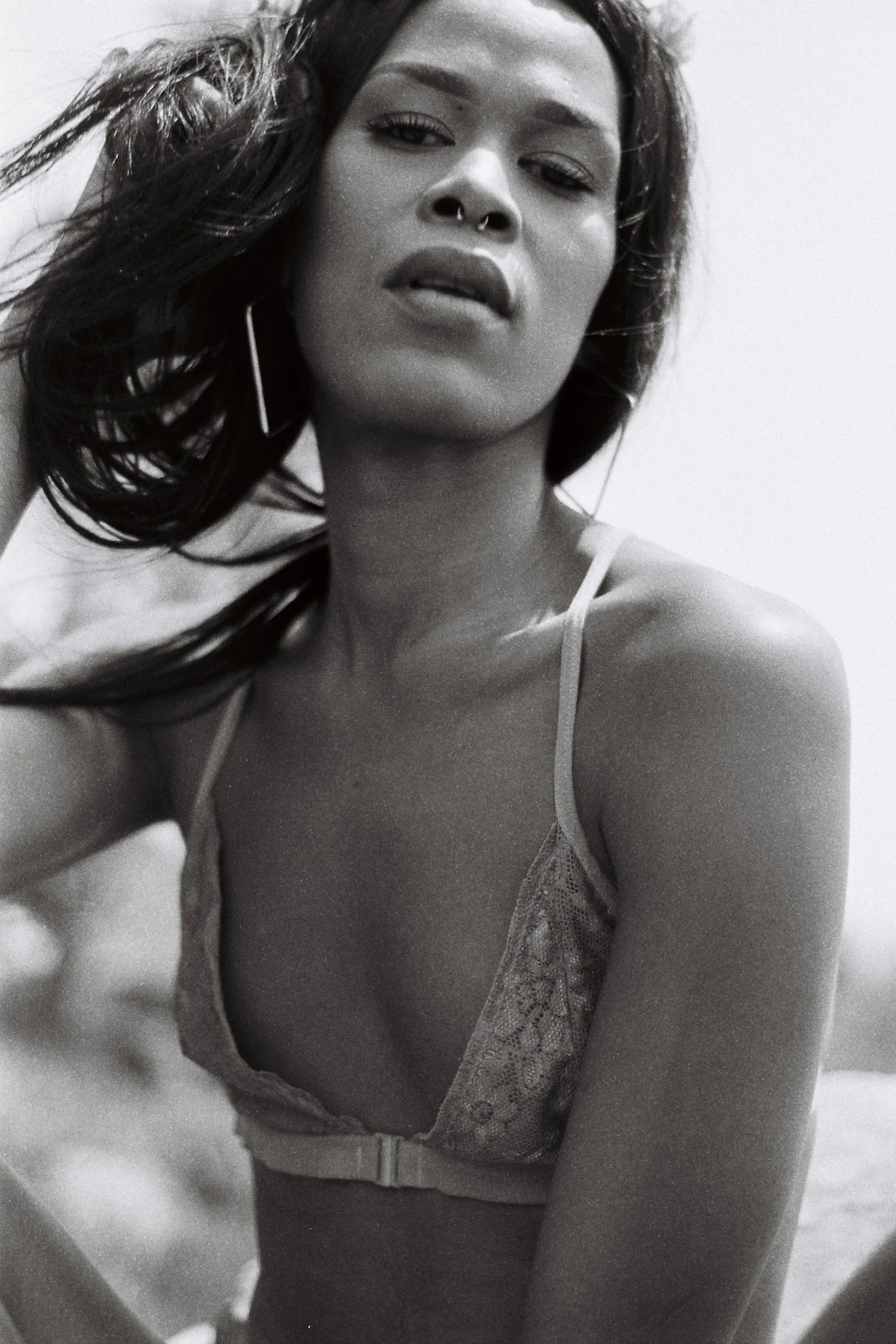

For Thozama, she sees herself as a Queer Cis-Woman. Her definition of the body is “the site of struggle.” Thozama’s main concern in the hardship of queer bodies today is that there are obstacles. “They exist in clothing, spaces we inhabit. They centre around the dialectic between safety and visibility,” she says.

Within the LGBTQ+ spectrum, bisexuality seems to be one of the identities that are always overlooked at and often frowned upon by many queer people. Mpho is one bisexual man who aims to challenge the idea of what it means to be bi and what it looks like. “I have always identified as such, doesn’t mean I’m closed off to other possibilities. I appreciate how fluid sexuality is,” he says. Mpho has become an active voice for black bisexual men, by documenting and creating platforms for bi visibility through social media and social change.

“I define my own body through notions of loneliness. Our bodies become the only thing that saves us, our home. We owe apologies to the body because we undermine its integrity and its agenda. In order to meet the image, fit a male gaze, the forms of change that I’ve gone through, I’ve harmed myself. I owe apologies to my body in the way that I undervalued it due to something that is beyond myself. A system.” says Mpho. We ought to learn more about ourselves and shake the tides that sweep at our self-loathing energies.

For Mpho, breaking out of toxic masculinity is done by doing the work. “Sometimes you have a choice to communicate something about your identity. There are expectations around masculinity. Your agency has been taken away. I’ve done active work to communicate who I am. The way I dress, the colours, the clothing, it gives a different idea of who I am.”

In much agency that is given or taken away, the barriers encountered from the past are still present right now, too. “People who centre themselves in other people’s experiences create challenges. As a Black person from a township, I can see how certain people (i.e. cis-het) centre themselves in queer people’s experiences and it creates this idea of queerness that impacts queer people’s progress, access to things like jobs. Queer people can exist in society but other people want to put forward a form of morality. African values are often used and misused to reject queerness, and that is an internalisation of the colonial past.” says Mpho.

These bodies represented are just a scratch of the surface of the diversity in our queer community in South Africa. Some choose to express their identities in different ways, such as art or performing or writing. Whatever the process might be, it’s important to note that what we’re seeing now is a revolution of young, brave and honest beings who are embracing their sizes, their struggles and harnessing their voices to be who they truly are… as heavenly as they want to be seen.